2. Variables and Data Types

Chapter 0010 2

Unfinished Chapter!!

I am actively working to complete this eBook, and I haven’t gotten to this chapter yet. In fact, it’s probably just a copy/paste from a similar chapter in my C# book.

In other words, don’t read this yet!

What’s the Point?

-

Write code to declare variables and assign values

-

Understand Python data types

-

Use standard Python naming conventions

-

Output variables using concatenation and interpolation

-

Do some basic math calculations

-

Get and process user input

Source code examples from this chapter and associated videos are available on GitHub.

It’s fun to create programs that display stuff on the screen, but that’s pretty limited. To start doing things that are more interesting—and useful—we’ll need to keep track of some information. In computer programming, information is called data, and data is stored in variables.

- variable

-

A piece of data that may change (or "vary") during program execution.

A variable has three parts:

-

A value

-

An identifier

-

A data type

2.1. Variable Values

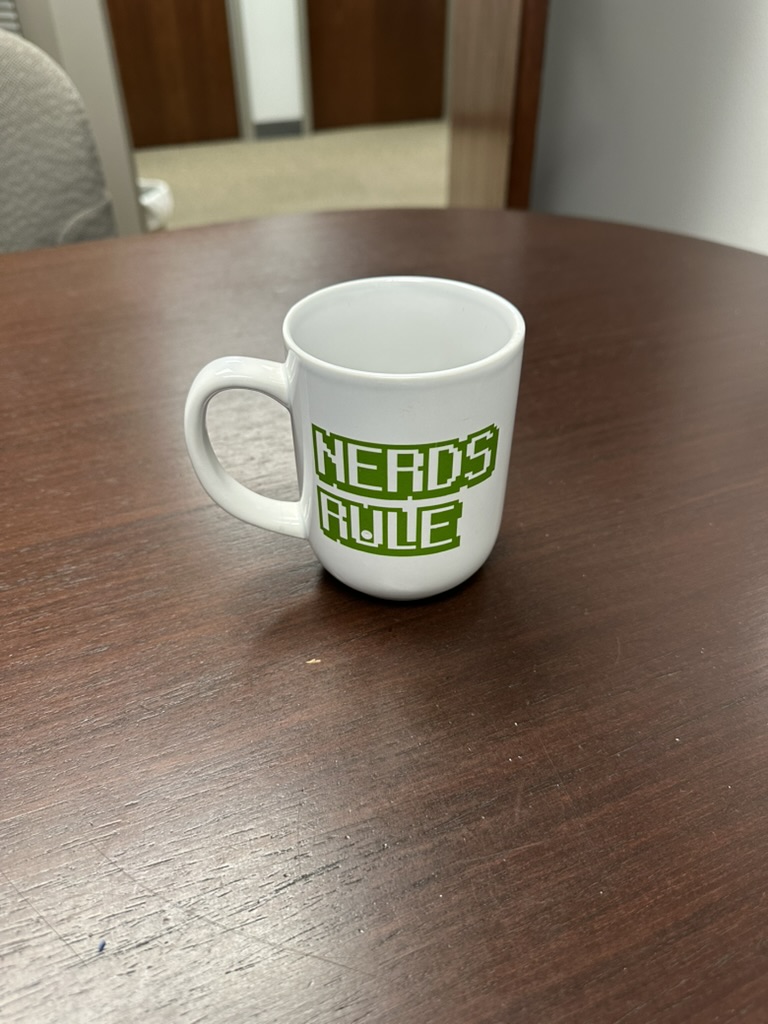

I encourage beginning students to think of a variable like a container, such as a cup.

The container can hold one thing at a time. We can put coffee in it, or we can put water in it—but we can’t put both in at the same time. If we start with coffee and decide we want to put water in there, the coffee gets dumped out and is gone forever. That’s fine, but we’d better make sure we don’t want the coffee anymore before we put something else in the mug.

A variable works the same way. It can hold one value, and that value can vary—that’s where the term comes from—but once it’s changed, that old value is lost.

I guess we could mix coffee and water, but then that’s really a new substance and we can’t get back our plain coffee (or our water). If we want to store coffee and water, we can do that by using two different containers.

From a programming perspective—rather than a coffee perspective—a variable is a location in the computer’s memory where we can store a value.

2.2. Variable Identifiers

In order to use that value, we have to know where to find it, so we give the memory location a name, technically called an identifier.

Variable identifiers or names are the character sequences that identify a variable. There are a few rules that determine whether or not an identifier is valid:

-

It can contain letters (upper or lower case), digits (0 - 9), and/or underscores (_).

-

The first character can’t be a digit.

-

It can’t contain whitespaces (tab, space, etc.) or special characters (like @, #, $, etc.) except for the underscore.

-

It can’t be a Python keyword or reserved word. These are words that are used in the Python language, like

ifandfor, and you’ll learn them as we go.

In addition to those technical rules about identifier names, PEP-8 states that variable identifiers should be all lowercase, with and underscore used to separate words.

By common practice, variable identifiers should be descriptive.

Single-letter variable names, like x for a number, are fine in your math class, but are generally not okay when you’re coding.

Examples of good variable names include: band_name, num_band_members, hourly_wage, and so on.

The expectation in my course is that your code will align with those conventions, because that’s what industry people expect. And you will lose points if you don’t.

2.3. Variable Values

Unlike many other languages, Python does not have a specific command for creating (or, as we will call it, initializing) a variable. Instead, the interpreter automatically makes a variable when we assign a value to it for the first time, and that’s done with an assignment statement.

An assignment statement, as the name suggests, assigns a value to a variable. The syntax for an assignment statement is an identifier, followed by the equals sign, followed by the value to assign. An assignment statement to create a variable for a grade point average might look like this:

gpa = 4.0

The interpreter will create the "container" called gpa and fill it with the value 4.0.

2.4. Variable Data Types

A variable is really just a location in computer memory where a piece of data is stored.

When we initialize a variable, the computer will need to know how much memory to set aside for it, and that depends on the kinds of values we want to store. Storing the number 7 doesn’t take very much space; storing a picture of John Elway takes a lot more space (but it’s worth it!).

The type of data we can store in a variable is called its

…drumroll, please…

data type.

In many other programming languages, the programmer specifies the data type.

In Python, the interpreter looks at a value and automatically determines the appropriate data type when we initialize the variable.

For our purposes at this time, there are three Python data types: int, float, and str, with additional types coming later.

2.4.1. The int Data Type

The int data type is for integers.

As you may remember from your math class, an integer is a whole number; that is, a number that doesn’t include any decimal places or fractional values.

5 is an integer and -824 is an integer, while 3.14 and 7 1/2 are not.

Python will automatically use an int when we are storing whole numbers.

int variables1

2

otis_redding_birth_year = 1941

billie_holiday_record_sales = 1200000

2.4.2. The float Data Type

The float data type refers to floating-point numbers.

A floating point number is a number that includes decimal data, such as 4.723 and -100.23.

A fraction like 7 1/2 can also be stored as a floating-point number, but only in decimal form (i.e., 7.5).

The Python interpreter will create a float when we’re initialize a variable with a decimal number.

float variables1

2

3

marias_gpa = 4.0

vinyl_record_rpm = 33.33

ticket_price_discount = -23.45

2.4.3. The str Data Type

The str data type, perhaps confusingly, refers to text data.

It gets its name because it can hold a bunch of characters put together, like a string of holiday lights.

So we pronounce this data type "string".

str variable is multiple characters strung together like a set of lights.A string can hold any characters: letters (upper and lowercase, which are different), digits (0 through 9), symbols (such as ^ and ), and a variety of special characters.

Since one of the characters a string can hold is a *space, we need a way to indicate the start and stop of a str.

In Python, we can use quotation marks, which coders often call double quotes, or apostrophes, which we call single quotes. Unlike many other languages, in Python it doesn’t matter which we use to denote our strings.

str variables1

2

drummers_name = "Charlie Watts"

address = '315 Bowery, New York, NY 10003, USA'

Use whichever symbol you want, but having both as options allows us to include quotes or apostrophes in our strings.

1

2

song_title = "That's alright" (1)

controversial_quote = 'John Lennon said, "We are more popular than Jesus now."' (2)

| 1 | This string includes an apostrophe |

| 2 | This string includes two quotation marks |

Both of those values are valid, but you can see the problem if you try to use the wrong one:

song_title = 'That's alright'

The interpreter will see the apostrophe after the word That and think it’s the end of the string; then it will get confused when it sees the additional characters s alright'.

You can indicate that a symbol is part of the string (and not the end of it) by using a backslash character in front of the symbol: song_title = 'That\'s alright'

|

Time To Watch!

Initializing Variables in Python [COMING SOON!]

2.5. Referencing and Outputting Variable Values

Initializing a variable with a value does not produce any output.

If we want to display the output of a variable we just put the identifier in a print() statement without any quotation marks:

1

2

3

4

5

6

artist_name = "Diana Ross"

birth_year = "1944"

print(artist_name)

print("was born in")

print(birth_year)

This code outputs

Diana Ross was born in 1935

Whenever the interpreter sees a variable identifier in a line of code, which we call a variable reference, it will look up the variable’s value in computer memory and essentially substitute it in place of the identifier.

In the first print() statement in the preceding code, it will see the identifier artist_name and retrieve the value "Diana Ross", which it then places into the print() statement.

2.5.1. Concatenating Output

We can combine the output into one statement by creating a string from multiple pieces using the + symbol.

1

2

3

4

artist_name = "Diana Ross"

birth_year = "1944"

print(artist_name + " was born in " + birth_year)

This will output all of the information on one line:

Diana Ross was born in 1935

Creating a str using the + symbol is called concatenating.

Python is assembling the different strings into one longer string.

In Python, we can only concatenate two strings together; it won’t work if we try to concatenate a number onto a string.

For that reason, the birth_year variable in this version of the code is initialized as a str using double quotes.

We’ll see a workaround for that later.

2.5.2. Interpolating Output

Another way to output variables and constants is to use interpolation.

Interpolation is a way to insert the value of a variable or constant into a string at a designated spot.

There are a few different ways to interpolate in Python, but the one we’ll use for now is called formatted string literals, commonly referred to as f-strings.

To use an f-string, we put the character f in front of the opening quotation mark of the string, and then we can put the variable identifier in curly braces { } in the position we want the value inserted.

1

2

3

4

artist_name = "Diana Ross"

birth_year = "1944"

print(f"{artist_name} was born in {birth_year}")

Because the f indicates that we want to interpolate values into the string, the interpreter will retrieve values to insert wherever it sees identifiers in curly braces.

For coursework in my class, you can use either concatenation or interpretation, but I encourage you to learn interpolation. It’s easier to read and write than concatenation and is considered the standard approach. Once you’ve gotten the hang of it, it’s very easy to use.

Time To Watch!

Outputting Variables in Python [COMING SOON!]

2.5.3. Choosing an Output Method

For our purposes, there’s no difference between outputting using separate print() statements, concatenation, or interpolation; you can use whichever approach you prefer (that gets the result you want).

Many programmers end up using interpolation because it’s easy to write—and easy to read—and it’s the newest approach, introduced in Python 3.6.

It also lends itself well to formatting output, which means making the output look nice and readable; we don’t worry about that here, but eventually you’ll find it useful.

For those reasons, interpolating with f-strings has become standard, and that’s what I’ll use for examples here. But if concatenation or multiple statements is easier for you, feel free to use those for now.

Take It for a Spin

This is a good time to stop and try out what you’ve learned so far. The Coding Practice assignment for this chapter can be completed with the concepts covered to this point.

Deep Cut

Python allows us to control how our output strings are formatted. We might want our numbers to show a certain number of decimal places (like two decimals for currency values) or include commas to make large numbers easier to read (like 1,000,000 instead of 1000000). And there are other formatting options as well. At this stage in our learning, we don’t worry about making our numbers look pretty, but you’re welcome to learn more about formatting strings.

2.6. Math Calculations

To start doing some calculations, we’ll use operators.

You can think of an operator as a symbol that performs a calculation or other action.

You’ve been using an operator already: the assignment operator, which uses the = symbol.

The action it completes is assigning the value on the right of the = symbol to the variable on the left.

Arithmetic operations work in a similar way.

In C#, there are five basic arithmetic operators:

| Operator | Description |

|---|---|

|

Addition |

|

Subtraction |

|

Multiplication |

|

Division (quotient) |

|

Modulo (remainder) |

The arithmetic operators work pretty much the way you’d expect, except maybe modulo—which might be a term you’ve never heard before. Each operator acts on the value to either side:

1

2

int sum = 5 + 7; (1)

int difference = sum - 2; (2)

| 1 | The value of sum will be 12 |

| 2 | The value of difference will be 10 (i.e., 10 - 2) |

2.6.1. Order of Operations

Early on in your math studies you learned about order of operations when an arithmetic expression has more than one calculation, and it works the same in C#. We call this operator precedence, and here are the guidelines:

-

Any operations enclosed in parentheses are evaluated first, following the rest of the rules here.

-

Multiplication, division, and modulus are evaluated next: the

*,/, and%operators. If there are more than one of these operations in the expression, they are evaluated from left to right. -

Addition and subtraction are evaluated last. As above, if the expression contains more than one

+or-operator, they evaluate from left to right.

Consider the following examples:

1

2

3

int result1 = 17 - 4 * 6 / 3; (1)

int result2 = 17 - 4 / 2 + 2; (2)

int result3 = 17 - 4 / (2 + 2); (3)

| 1 | result1 is 9: 4 * 6 is 24, then 24 / 3 is 8, and then 17 - 8 is 9. |

| 2 | result2 is 17: 4 / 2 is 2, then 17 - 2 is 15, and then 15 + 2 is 17. |

| 3 | result3 is 16: (2 + 2) is 4, then 4 / 4 is 1, and then 17 - 1 is 16. |

2.6.2. More Arithmetic with Less Typing!

There’s a pretty consistent rule of thumb in coding that says programmers want to type as little as possible, so programming languages often provide shorthand ways of writing code that’s used frequently.

Compound assignment operators (also called shorthand operators) simplify the syntax when you need to change a variable’s value relative to it’s existing value.

For example, if we want to add 10 to a weight variable that already has the value 145, we could use the following:

weight = weight + 10;C# starts on the right side of the assignment expression and retrieves the current value of weight, which is 145, adds 10 to that value, and stores the result back in weight.

We can combine the addition operator (`) with the assignment operator (`=`) to make a compound addition operator: `=, which allows us to rewrite the above line of code as:

weight += 10;You can use compound assignment operators for all of the arithmetic operations.

| Operator | Description |

|---|---|

|

Adds the value on the right to variable value on the left |

|

Substracts the value on the right from the variable on the left |

|

Multiplies the value on the left by the value on the right |

|

Divides the variable value on the left by the value on the right. |

|

Divides the variable value on the left by value on the right, then assigns the remainder. |

An operation we might not use much now, but will start using a lot when we learn to write loops, is incrementing a value, or adding 1 to a value. The increment operator (two plus symbols) gives us a very easy way to do that. On somebody’s birthday, for example, we could write:

age++;The ++ operator simply adds 1 to the current value of age.

The decrement operator is —, and it subtracts 1 from a variable’s value.

If we’re counting down the number of days until our next birthday, we could execute this expression each morning:

daysRemaining—;Increment and decrement only require one operand, so we call them unary operators.

There are two forms to the increment and decrement operators: prefix and postfix. These examples use the postfix form, putting the operator after the variable name, whereas a prefix form would have the operator before the variable name: ++age. There’s a subtle difference in how postfix and prefix operations work, but for now you can use them interchangeably. I mention it here only because you might see code examples online using the prefix form.

|

2.7. Handling User Input

Until now, our code hasn’t been interactive—each execution of a program results in the exact same output, and the user never has the chance to input anything.

To produce output, we’ve been using Console.WriteLine and Console.Write to display text on the screen.

For input, we’ll use Console.ReadLine (and, occasionally, Console.Read).

1

2

3

4

string artist = "";

Console.Write("Enter the name of your favorite music artist: ");

artist = Console.ReadLine();

Console.WriteLine($"Your favorite music artist is: {artist}");

Console.ReadLine only deals with string values; even if the user types in a number, it will be stored as a string—which means we’ll need to convert it to a number if we want to do any math with it.

1

2

3

4

5

int age = -1;

Console.Write("Enter your age: ");

age = Console.ReadLine(); (1)

age++;

Console.WriteLine($"Next year you will be {age}");

| 1 | This code will not compile because Console.ReadLine returns a string, but we’re trying to assign it to an int. |

2.7.1. Converting Data Types

When we looked at arithmetic, we saw that data types are really important.

For example, if we divide an int by another int, the result is an int—even if we stick that result in a double variable.

And we learned that we can use a process called type casting to help switch between two numeric types.

But we can’t just cast a string to numeric type because the string might not contain a number—it might have letters and weird symbols.

Instead, we need to use a method to convert the string to a number.

There are two basic ways to do the conversion: with the Convert class or with the Parse method.

The Convert class has a few methods for converting values.

The two we’ll use most are:

-

Convert.ToInt32, which can convert astringto anint. -

Convert.ToDoublewhich can convert astringto adouble.

The 32 in ToInt32 is the number of bits used to store the number, and that’s the size of the int data type. There are methods to convert to 16-bit and 64-bit integers as well, though we won’t be using them.

|

Convert class 1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

int age = -1;

double gpa = -1.0;

Console.Write("Enter your age: ");

age = Convert.ToInt32(Console.ReadLine());

age++;

Console.WriteLine($"Next year you will be {age}");

Console.Write("Enter your GPA: ");

gpa = Convert.ToDouble(Console.ReadLine());

gpa += 0.5;

Console.WriteLine($"If you improve by half a letter grade, you GPA will be {gpa}");

We can also use the Parse method to convert a string to a number.

The Parse method is a little different because it is called on the data type we want to convert to, rather than using a class method.

If we are converting from a string to an int, the syntax is int.Parse().

For a double, it would be double.Parse().

Parse method 1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

int age = -1;

double gpa = -1.0;

Console.Write("Enter your age: ");

age = int.Parse(Console.ReadLine());

age++;

Console.WriteLine($"Next year you will be {age}");

Console.Write("Enter your GPA: ");

gpa = double.Parse(Console.ReadLine());

gpa += 0.5;

Console.WriteLine($"If you improve by half a letter grade, you GPA will be {gpa}");

There are some differences between the two approaches, but for our purposes, they’re interchangeable. You should recognize both, but you can use whichever you prefer in your code.

Check Yourself Before You Wreck Yourself (on the assignments)

Chapter Review Questions

Sample answers provided in the Liner Notes.